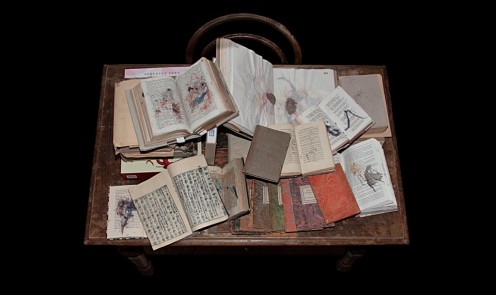

Miloš Šejn: Books

3 Jul – 3 Aug 2014

This exhibition takes place at Art Archive at DOX.

The work of Miloš Šejn is wedded to nature, more precisely to landscape, but an interpretation that would restrict itself to this connection would be a simplified and impoverished one. It is not only that places seemingly untouched by man, where Šejn’s scenes take place, were often inhabited long ago (for example, Prachovské skály, various caves), so interaction with them is also contact with history; but the important thing is mainly the utilization of landscape as a means of coming to terms with oneself.

Because nature most naturally shows itself to man as landscape, i.e. shows itself to those who pass through it, and thus moves in a network of relationships that create it, this means that it appears in sequence. Walking is thus a sequence of steps, or a sequence of views of the landscape, a sequence of spaces observed from shifting angles. The ideal medium for their capture thus seems to be the book, or as we know from Carrión, a sequence of spaces.

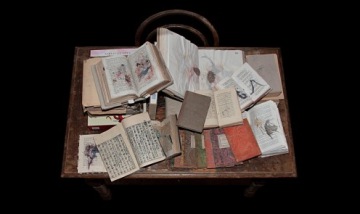

In his work, Miloš Šejn used books with blank pages as well as books that already had content. But this content is however not without its effect on the artist’s drawings in interaction with the landscape. It isn’t about specific use of text – reading or recital of memorized passages, but about the intermingling of the sum total of the given text with the artist’s meditation, his movement and his drawing.

Drawings and writing recording shapes and feelings from the observed natural environment using material available on the spot (plants, soil) is a characteristic of Šejn’s books; he originally used this process during the creation of large individual drawings created in one location, in direct contact with the ground.

When reading a written message, we first recognize characters, then we reconstruct words, and finally ideas; but reading a manuscript is also a path tracing the writer’s physical movement. In the case of Šejn’s drawings/notes, it is a sort of synthesis of kinetic reconstruction: we follow the movement of his hand captured with materials that are part of the landscape that the artist walked through, and we follow this movement through space (where walking itself is a reading of the landscape) when we page through a book.

But the excursion that we reconstruct is not direct. Detours, even a conscious effort to lose oneself in the landscape, aren’t an error and waste of time for Šejn, but rather a way of connecting oneself with given places, to become part of them. Wandering in the Buddhist sense could be understood as a manifestation of blindness (moha), because this includes an insistence on man’s separation from this environment, the faith that the world outside us is also against us. The insistence on a separate personality is only seemingly in defiance of chaos; giving something up also means accepting something; the detachment of which Miloš Šejn is capable can be a means of interconnecting immediate experience with the world, overcoming duality.

Lucie Rohanová