Jan Tarasin: Seeing the World

3 Feb – 2 Mar 2014

Exhibition takes place in the Art Archive at DOX.

Exhibition opening: 3 February, 4.30 pm.

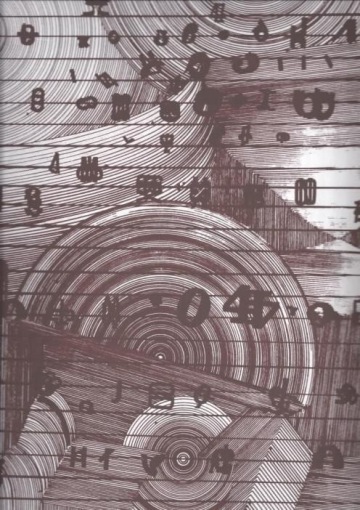

Jan Tarasin observes nature. Nature is a broad concept; it includes people, various geometric shapes, symbols... Jan Tarasin is a thinker who in his notions of visual art takes similar paths as theoreticians of a systematic approach in science, especially the natural sciences. Because Jan Tarasin is above all an artist, his observation has an unavoidable component of recording, through the creation of new systems, original, his own, but wedded to those already existing in the world prior to its image (and according to the author, this creation provides the same sensory joy as for example landscape painting).

These original books, sets of graphic works that Tarasin calls sketchbooks, contain a cross-section through his subject matter, which is quite varied but with the common denominator being Tarasin’s perspective, which is decisive for understanding his visual language.

The position of the observer, the beginning of all seeing, is also a subject of Tarasin’s theoretical considerations and a key to images that are intentionally beyond European tradition, which has developed as a prisoner of the horizon. The Renaissance invention of perspective, looking at the world from horizon to horizon, is an anthropocentric one. However, over the course of history the notion of man as master and centre of events becomes not only untenable, but frustrating: we began to realize that we cannot touch the world via a perspective that grows smaller and smaller until it disappears – however far we run to catch up, it always eludes us.

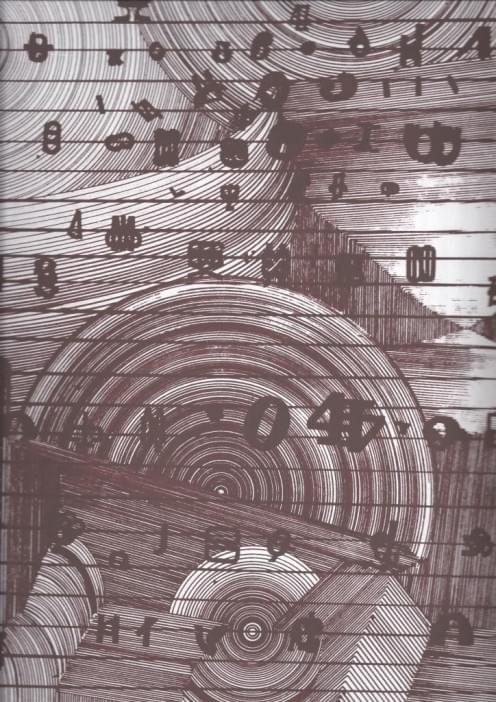

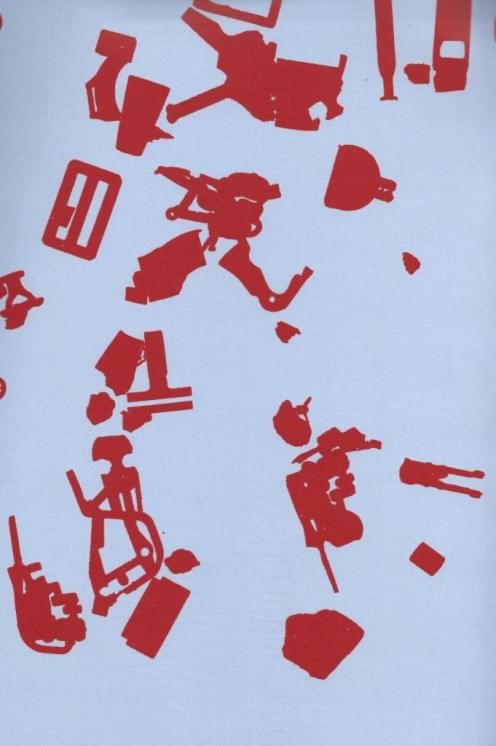

Tarasin realized this, and so does not attempt to capture all the world’s concrete features, as an itemized list (the name of one of his works, Counted Items, is ironic) – but rather as a system. However, even the world’s system cannot be captured as a whole. Just like a viewpoint in perspective mode is just a subset of reality, a systematic viewpoint is also a certain subset. A group of elements that are interesting and important for a given purpose is selected, elements that are interrelated. This is a general principle, however. Tarasin’s subsets therefore do not capture a part of the world that is specific and different from everything else, but a sample of the system as such. Often, this involves depicting structure as we normally understand this term - the grain in wood, a chain-link fence, an emphasized raster print pattern, a cluster of symbols and neo-symbols, musical notes, regularly spaced birds on wires... at other times it is a flock of birds in flight or a house of cards that can fall apart at a moment’s notice – the structure is not always of the same type (“it is impossible to create a universal system”) and is not permanent, much less unchanging – it is omnipresent, though; it doesn’t represent the entire global system, but merely refers to the system as a principle of seeing.

Another important aspect of systemic observation is the realization of the zoom: each element of the system is itself composed of other elements – which reminds us of Tarasin’s fragments of letters and items that he elsewhere combines into neo-symbols and neo-items composed of relatively familiar elements – but differently. To reveal hitherto disguised relationships between objects, Tarasin also uses the opposite approach – the rhythm of books in a library inter-reacts with the rhythm of a graphical raster, the rhythm of lines marks out a room, which is in turn covered by a rhythm of neo-symbols, a set of tin soldiers changes the features of a human face. “The world around us is composed of many structures that overlap, interpenetrate, opposing each other as well as depending on each other,” says Tarasin. “We’re happy when we discover and recognize a fragment of the system and unhappy when it disintegrates or disappears.” The desire to comprehend the world’s system is inherent to the human mind, which wants to appropriate the observed, but since Renaissance times our methods have changed. We no longer find it enough to merely record (be it shapes or impressions), because our cognition has changed – as has our way of seeing.

Lucie Rohanová